Roofing is often treated as a finishing choice—color, style, warranty length. In sustainable building, it's better understood as a high-impact environmental system. A roof governs how a building exchanges heat with its surroundings, how long the envelope stays watertight and efficient, and how often materials must be replaced and discarded. Because it is continuously exposed to sun, wind, rain, and temperature cycling, the roof's performance influences both operational emissions (energy used year after year) and embodied emissions (carbon released to manufacture, transport, and install materials).

Why roofing choices significantly impact environmental performance

Roofs matter disproportionately because they sit at the most intense point of environmental exposure:

- Solar load: Roofs receive more direct solar radiation than most walls, especially on low-slope buildings.

- Thermal stress: Daily heating and nighttime cooling drive expansion/contraction, accelerating material fatigue.

- Moisture management: Roof failures can degrade insulation and interior finishes, multiplying waste and repair impacts.

Replacement frequency: Roofing is one of the most commonly replaced building components; short-lived roofs create repeated material throughput and landfill burden.

A sustainable roofing decision therefore isn't just "choose a greener material." It's a choice that affects energy demand, durability, maintenance labor, and end-of-life waste for decades.

The connection between roofs, energy efficiency, and carbon footprint

A building's carbon footprint has two dominant contributors:

- Operational carbon: emissions associated with heating and cooling energy over the building's life.

- Embodied carbon: emissions from producing and installing materials (and replacing them later).

Roofing influences both. A roof that reduces heat gain in summer can lower cooling energy and peak electricity demand. A roof that remains intact and watertight for 40–70 years avoids multiple tear-offs and replacement cycles, reducing embodied carbon and construction waste. The most sustainable roofs typically combine high thermal performance with long service life and credible end-of-life recovery options.

Understanding Eco-friendly Roofing Materials

"Eco-friendly" is frequently used as a marketing term, but in construction it should mean something measurable: a material or system that minimizes environmental impact across its lifecycle while maintaining reliable performance in real-world conditions.

What "eco-friendly" means in construction contexts

In a construction context, eco-friendly roofing usually implies:

- Lower lifecycle emissions: reduced embodied carbon and/or reduced operational energy demand.

- Responsible sourcing: renewable feedstocks, recycled content, or verified supply chains.

- Long-term performance: durability that prevents premature replacement and associated waste.

- Healthy chemistry and compliance: reduced hazardous substances and compatibility with modern codes and standards.

- End-of-life pathways: realistic recyclability, reuse potential, or low-impact disposal.

Importantly, a roof can be "eco-friendly" either by being very efficient, very long-lasting, or ideally both.

Renewable, recycled, and recyclable roofing materials

These categories are related but not interchangeable:

- Renewable materials come from feedstocks that can be replenished on human timescales (e.g., responsibly sourced wood). Sustainability depends on forestry practices, land use, and treatment chemistry.

- Recycled materials incorporate pre- or post-consumer waste streams (e.g., metal roofing with recycled content; some synthetic/composite shingles). This can reduce demand for virgin extraction and lower embodied energy—especially when recycled content is high and supply chains are efficient.

- Recyclable materials can be recovered at end of life, but recyclability depends on local infrastructure and whether the roof assembly is easy to separate and uncontaminated.

In practice, the strongest options often combine recycled content + high likelihood of end-of-life recovery, supported by documentation rather than assumptions.

Environmental impact across the material lifecycle

A lifecycle view typically considers four phases:

- Raw materials and manufacturing: energy intensity, emissions, water use, and waste from production.

- Transport and installation: weight, distance traveled, jobsite waste, and installation complexity.

- Use phase: impact on heating/cooling energy; maintenance needs; resilience to local hazards.

- End of life: reuse, recycling, landfill burden, and ease of material separation.

This is why two roofs with similar upfront "green" claims can have very different outcomes. A roof that lasts 50 years with modest maintenance can outperform a lower-impact material that must be replaced twice in the same period.

Key Factors to Consider When Choosing a Sustainable Roofing Option

Selecting a sustainable roof is a fit problem: the best option is the one that matches your climate, building constraints, budget horizon, and regulatory goals—while delivering dependable performance.

Climate and geographic conditions

Climate determines which roof strategies produce real environmental gains:

- Hot/sunny climates: Prioritize solar reflectance, thermal emittance, and ventilation strategies to reduce cooling loads. "Cool roof" approaches often deliver meaningful operational savings.

- Cold/heating-dominated climates: Focus on air sealing, insulation continuity, ice-dam resistance, and moisture control. Reflective surfaces may still help in summer but might not be the primary driver of annual savings.

- Coastal or industrial environments: Corrosion resistance, coating systems, and compatible fasteners become sustainability issues because corrosion-driven failure shortens life.

- High-wind or hurricane regions: Attachment methods, tested uplift ratings, and edge details often matter more than the nominal material category.

- Hail and severe storm zones: Impact resistance and repairability affect replacement cycles and insurance-driven tear-offs.

A "green" roof that performs poorly in local hazards is not sustainable; it becomes a repeat construction project.

Building type and structural requirements

Structure and geometry narrow the field:

- Roof slope: Some materials suit steep-slope residential roofs; others dominate low-slope commercial applications.

- Load capacity: Heavy systems (e.g., tile, slate, or vegetated roofs) can require structural reinforcement, which adds cost and embodied impact.

- Mechanical equipment and penetrations: Commercial roofs often carry HVAC units, vents, and piping—details that increase leak risk if the system is not designed for service access and durable flashing.

Sustainability improves when the roof is designed as an assembly (deck + air/vapor control + insulation + waterproofing + drainage + finish), not as a standalone product.

Budget, lifespan, and lifecycle cost

Sustainable decision-making is strongest when it uses lifecycle cost, not price-per-square:

- First cost: materials, labor, tear-off, and any structural upgrades.

- Maintenance cost: coatings, cleaning, inspections, and repair frequency.

- Energy cost: heating/cooling reductions from reflective or insulating strategies; potential on-site generation if solar is involved.

- Replacement cost: how often you pay for demolition, disposal, and disruption.

If the ownership horizon is long, durability and maintenance stability become top priorities. If it's shorter, energy savings and market acceptance may dominate—while still meeting code and resilience needs.

Local regulations and green building standards

Codes and standards can strongly influence "best choice":

- mandated reflectivity levels for certain climate zones or building types,

- fire ratings and wildfire-interface requirements (especially relevant to wood products and certain assemblies),

- stormwater rules that can make vegetated roofs attractive,

- green building programs that reward recycled content, energy performance, and durable envelope strategies.

Align material selection with the documentation required for permits, incentives, and sustainability reporting.

|

Decision Factor |

Key Sustainability Considerations |

|

Climate & Location |

Hot climates favor reflective, ventilated roofs to cut cooling loads; cold climates prioritize insulation and moisture control. Coastal, high-wind, or hail-prone areas require corrosion resistance, impact durability, and proven attachment systems. |

|

Building Type & Structure |

Roof slope, load capacity, and penetrations limit material choices. Heavier systems may need reinforcement, while commercial roofs require durable detailing around equipment and service areas. |

|

Budget & Lifecycle Cost |

Sustainable value comes from lifecycle analysis—balancing upfront cost, maintenance needs, energy savings, and replacement frequency over the building’s ownership horizon. |

|

Codes & Green Standards |

Local codes may dictate reflectivity, fire ratings, stormwater control, or recycled content. Align roofing choices with compliance, incentives, and sustainability certification requirements. |

Energy Efficiency and Thermal Performance

Energy performance is where roofs can deliver long-term environmental returns. The roof affects both heat gain (summer) and heat loss (winter), and it also influences peak HVAC demand, which has outsized grid impacts.

How roofing affects heat gain and heat loss

Roofs control heat transfer through:

- Radiation: sunlight absorbed by the roof surface and re-radiated as heat.

- Conduction: heat flowing through roof layers into the building.

- Convection and air leakage: heat transfer driven by airflow, often through gaps and poorly sealed details.

Even high-quality insulation performs poorly if air leakage and moisture are unmanaged. From a sustainability standpoint, airtightness and moisture control are "invisible" features that protect thermal performance over time.

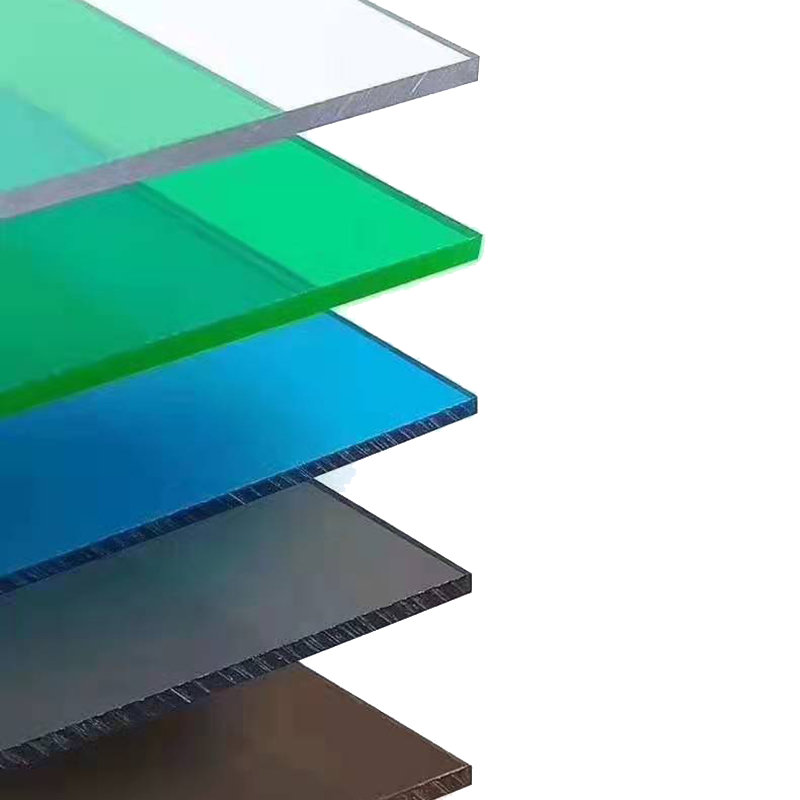

Reflective vs insulating roofing systems

Reflective and insulating strategies solve different problems:

- Reflective (cool roof) strategy: Reduce solar absorption at the surface, lowering roof temperature and cooling demand. This is often most effective for low-slope roofs in warm climates.

- Insulating strategy: Reduce heat transfer year-round by increasing thermal resistance and maintaining continuity. This is critical in both heating and cooling climates.

The best designs frequently combine both: adequate insulation plus a surface that manages solar load, tailored to climate and building use.

Role of cool roofs and thermal mass

- Cool roofs can reduce peak rooftop temperatures and lower cooling loads. They also help mitigate urban heat island effects when used at scale. Performance depends on maintaining reflectivity (soiling and aging matter) and designing the assembly to manage moisture.

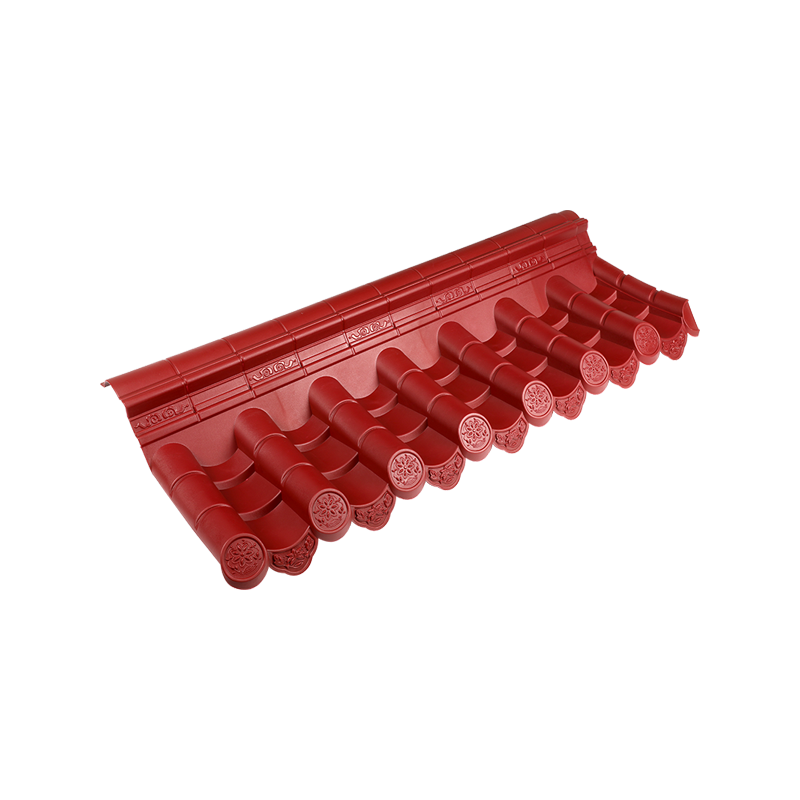

- Thermal mass (as in tile, concrete assemblies, or certain roof build-ups) moderates temperature swings by absorbing and releasing heat more slowly. Thermal mass can improve comfort and reduce peak loads, but it is not a substitute for insulation; it works best when integrated with ventilation and appropriate underlayment design.

Sustainable thermal performance is ultimately system performance, not a single-material attribute.

Material Durability and Service Life

Durability is an environmental strategy. The carbon cost of manufacturing and installing a roof is paid upfront; the longer the roof performs, the more that "carbon investment" is spread across years of service.

Why longevity is critical to sustainability

A short-lived roof multiplies impacts:

- repeated manufacturing and transport emissions,

- repeated tear-offs and landfill waste,

- repeated disruption and labor,

- higher risk of moisture damage to insulation and interiors.

Longevity is especially valuable when paired with energy performance: a roof that remains intact and efficient for decades preserves the building's thermal envelope and prevents hidden performance losses.

Maintenance demands and replacement cycles

Maintenance is not a drawback if it is predictable and modest; it becomes a sustainability issue when neglect leads to early failure. Sustainable planning includes:

- routine inspections (especially after severe weather),

- maintaining flashings, sealants, and drainage paths,

- cleaning or recoating when required to preserve reflectivity or waterproofing performance.

A roof system with a clear maintenance plan often achieves a longer service life than a theoretically "better" material installed without long-term care.

Weather resistance and climate adaptability

Climate adaptability is durability in real-world form. A sustainable roof should be selected for:

- UV and heat cycling resistance in hot climates,

- freeze-thaw resilience where temperatures cross 0°C frequently,

- wind uplift resistance in storm-prone regions,

- corrosion resistance near saltwater or industrial pollutants,

- fire performance where wildfire risk is significant.

When a roof is matched to local stressors, it fails less, lasts longer, and generates less waste—exactly what sustainability is supposed to accomplish.

Environmental Impact of Roofing Materials

Roofing sustainability is best evaluated through a lifecycle lens: where materials come from, how they are made, how they perform during decades of use, and what happens when they are removed. A roof that looks "green" at purchase can still carry a heavy footprint if it requires frequent replacement or cannot be recovered at end of life.

Raw material sourcing and extraction

Extraction impacts vary dramatically by material type:

- Metals require mining and refining, which can be energy-intensive, but they also benefit from mature recycling loops that reduce reliance on virgin ore.

- Clay, slate, and aggregates are typically quarried. Quarrying can disturb habitats and landscapes, yet these materials are inert and often long-lived, which can dilute impacts over time.

- Wood can be a low-impact, renewable feedstock when sourced from responsibly managed forests, but it becomes problematic when harvesting is poorly managed or when heavy chemical treatments are required for code compliance.

- Petrochemical-based synthetics shift extraction impacts upstream to oil and gas. Using recycled polymer feedstocks can reduce virgin extraction demand, but the overall benefit depends on recycled content, additives, and realistic end-of-life pathways.

Sustainability in sourcing is strongest when projects prioritize verified supply chains, regional availability (to reduce transport), and materials that do not force premature replacement.

Manufacturing energy and emissions

Manufacturing often dominates embodied emissions:

- Metal production can be high-energy, but recycled metal typically requires far less energy than producing metal from virgin ore.

- Cement-based products (concrete tiles) carry emissions tied to cement production. Their environmental case relies on longevity and performance, plus any lower-carbon cement strategies available in the supply chain.

- Fired clay requires kiln energy; again, long service life and low maintenance are what help its lifecycle profile.

- Solar roofing involves energy-intensive component manufacturing, but it can offset operational emissions by producing clean electricity—its sustainability depends on system life, output, and grid conditions.

- Membranes/coatings for cool roofs vary widely by chemistry; their footprint is strongly influenced by service life, recoating frequency, and VOC/compliance profiles.

- A practical rule: the greener manufacturing story matters, but service life and performance stability often matter more across 30–60 years.

End-of-life recyclability and waste reduction

End-of-life outcomes are shaped by both material and assembly design.

- High-recovery potential: metals (high value, widely accepted), some clean mineral materials (reuse potential), certain PV components (growing but uneven recycling infrastructure).

- Conditional recovery: wood (can be reused or downcycled if uncontaminated; treated wood complicates disposal), synthetics/composites (recyclability depends on formulation and local capability).

- Waste reduction strategies: design for disassembly, avoid unnecessary composite layers, keep documentation for future sorting, and select systems that can be repaired rather than replaced.

The most sustainable end-of-life is often the one you delay the longest—by choosing a roof that is repairable and durable.

Overview of Common Eco-friendly Roofing Materials

Eco-friendly roofing isn't one category; it's a toolbox. Below is a performance-oriented overview of the most common options and what typically makes each one "green" when specified correctly.

- Recycled metal roofing

- Recycled metal roofing leverages a circular materials advantage: high recycled content and strong end-of-life value. When paired with reflective finishes and a well-ventilated assembly, it can also reduce cooling loads. It tends to shine in durability, fire resistance, and long-term recyclability.

- Clay and concrete tiles

- Tiles are mineral-based and extremely weather tolerant in many climates. Their sustainability value is often longevity-driven: long service life and resistance to UV and rot. Thermal mass can help moderate indoor temperature swings when the roof assembly is designed for it.

- Green (living) roof systems

- Green roofs add a vegetated layer over waterproofing. Their sustainability benefits extend beyond energy: stormwater retention, urban heat reduction, and potential biodiversity value. They require careful structural design and a realistic maintenance plan.

- Solar roofing technologies

- Solar roofing (panels or solar shingles) reduces operational emissions by generating on-site electricity. Sustainability depends on roof orientation, shading, local electricity carbon intensity, and aligning PV life with roof life so the system is not removed prematurely due to re-roofing.

- Slate roofing

- Slate is a natural stone with exceptional longevity. Its environmental case is straightforward: it is inert and can last so long that replacement cycles (and their waste) are minimized. Upfront impacts are tied to quarrying, transport weight, and specialized labor.

- Sustainably sourced wood shingles

- Wood can be renewable and lower in embodied energy when responsibly sourced. However, sustainability depends heavily on certification, climate fit, fire code requirements, and long-term maintenance. Treated products may be necessary in many regions, affecting end-of-life options.

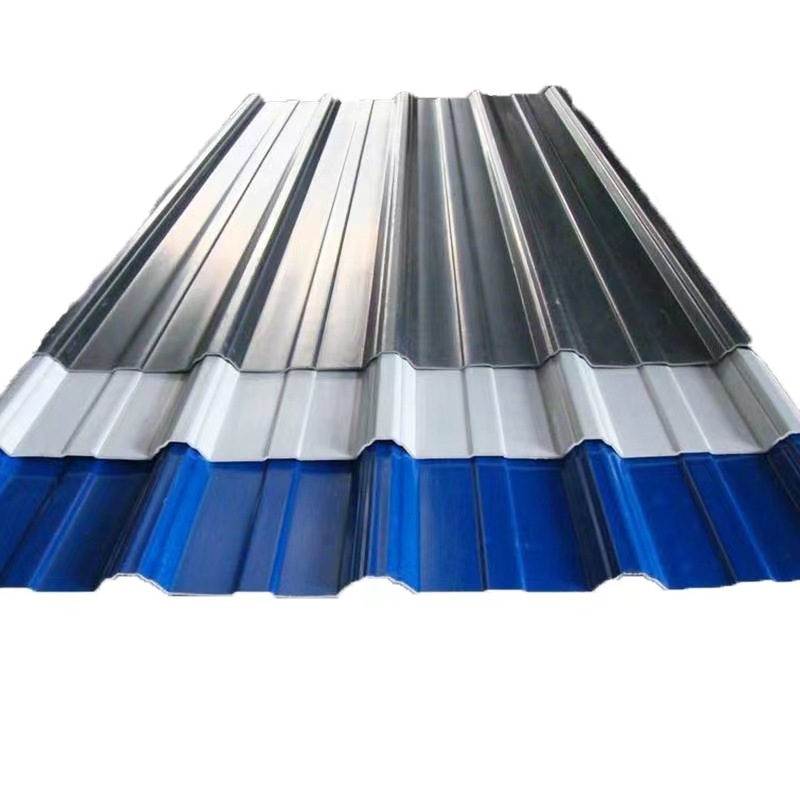

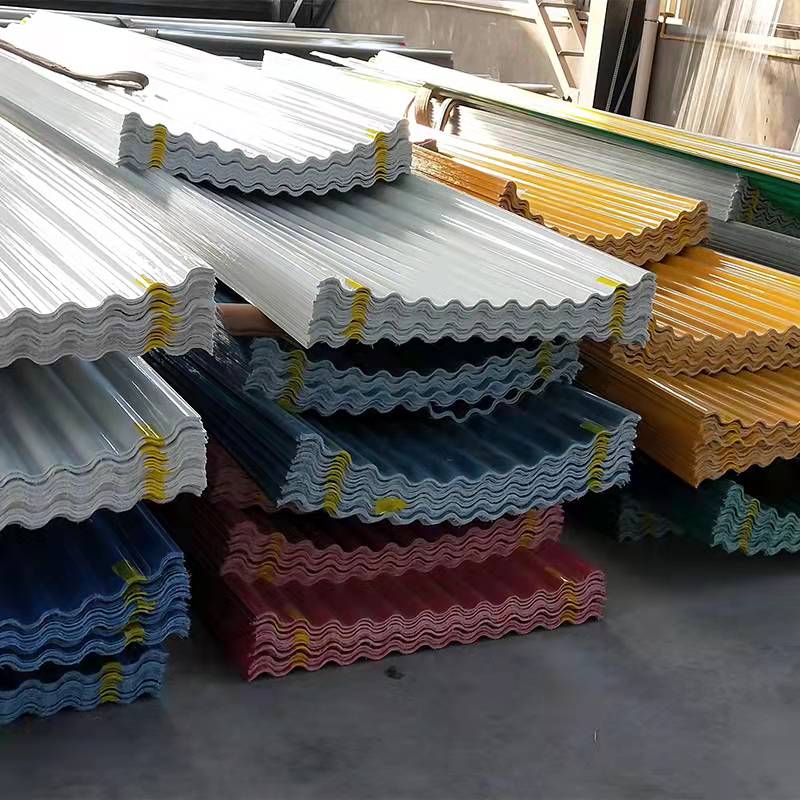

- Synthetic roofing made from recycled materials

- Synthetic shingles/tiles made with recycled polymers can divert waste streams and reduce weight compared to slate or tile. Performance varies by product quality and formulation. Key sustainability questions are recycled-content transparency, longevity, and whether the material can be recovered at end of life.

Comparing Eco-friendly Roofing Materials by Performance

Sustainability decisions improve when you compare materials on the factors that most influence lifecycle outcomes: energy performance, durability, structural demands, and architecture.

Energy efficiency comparison

Energy performance comes from two sources: reducing heat gain/loss and generating energy.

- Strong cooling-load reduction: cool roofs (reflective membranes/coatings), reflective metal, some light-colored tiles, and green roofs (through shading and evapotranspiration).

- Year-round envelope stability: systems that support robust insulation and airtight detailing—material choice matters, but assembly detailing matters more.

- Energy generation: solar roofing is unique; it can reduce net building emissions even if its embodied footprint is higher.

Durability and maintenance comparison

Durability is sustainability's quiet multiplier.

- Very high longevity (often): slate, quality metal, properly installed tile.

- System-dependent longevity: cool roofs (varies by membrane/coating and maintenance), green roofs (often extends membrane life but adds maintenance).

- Higher maintenance sensitivity: wood (moisture/fire constraints), green roofs (planting/drainage upkeep), and PV (monitoring and occasional electrical service).

Maintenance should be treated as a planned operating cost, not an afterthought.

Weight and structural load considerations

Structural load can be the hidden sustainability trade-off: if a roof requires reinforcement, the added materials and labor can offset some environmental gains.

- Heavier systems: slate, clay/concrete tile, green roofs (especially saturated loads).

- Moderate to light: metal roofing, most cool roof membranes, many synthetic products.

- Solar: panels add load; typically manageable, but verification is essential—especially on older buildings.

Visual and architectural impact

A roof is part of a building's identity and sometimes a planning constraint.

- Traditional/high-end aesthetics: slate, clay tile, wood (where allowed).

- Modern/industrial or versatile: metal (many profiles), cool roof membranes (often low-slope), synthetics (mimic slate/shake/tile).

- Visible technology expression: solar can be subtle or prominent depending on product choice, layout, and roof geometry.

- Landscape integration: green roofs can change the building's relationship with its surroundings, especially on low-rise urban projects.

To make comparisons easier, here is a compact decision table (generalized—final selection should be climate- and assembly-specific):

|

Material |

Energy Impact |

Durability / Maintenance |

Structural Load |

Architectural Fit |

|

Recycled metal |

High (reflective options) |

High durability, low maintenance |

Low–medium |

Wide range |

|

Clay/concrete tile |

Medium–high (thermal mass, color) |

High durability, moderate repairs |

High |

Traditional/mediterranean |

|

Green roof |

Medium–high (cooling + stormwater) |

Higher maintenance, design-critical |

High (esp. saturated) |

Contemporary/urban |

|

Solar (panels/shingles) |

Very high (energy generation) |

Moderate maintenance, monitoring |

Medium |

Varies by integration |

|

Slate |

Medium (longevity-driven) |

Very high durability, specialist repair |

High |

Historic/premium |

|

Certified wood |

Medium (assembly-dependent) |

Maintenance-sensitive, fire constraints |

Medium |

Rustic/traditional |

|

Synthetic recycled |

Medium (color/assembly) |

Medium–high (varies by product) |

Low–medium |

Mimics many styles |

|

Cool roof systems |

High in hot climates |

System-dependent; coatings need upkeep |

Low |

Mostly low-slope |

Cost Considerations and Long-term Value

Sustainable roofing is often a lifecycle value decision disguised as a material selection. The cheapest roof per square meter can be the most expensive roof over 30 years once energy, maintenance, and replacement are counted.

Upfront cost vs lifetime value

Upfront costs typically rise with weight, installation complexity, and specialized labor (e.g., slate, tile, green roofs, integrated solar shingles). Lifetime value rises with:

- long service life and repairability,

- stable performance (no rapid degradation of reflectivity or waterproofing),

- resilience (reduced storm/fire losses and fewer emergency replacements),

- compatibility with future upgrades (solar-ready detailing, easy reroof sequencing).

A useful framing is cost per year of service, not cost at purchase.

Energy savings and return on investment

Energy ROI depends on climate and building operation:

- In cooling-dominated climates, cool roofs and reflective metal often provide quick operational savings by reducing peak heat gain.

- Solar ROI depends on electricity pricing, incentives, shading, and interconnection rules; it can be compelling when roof life and PV life are aligned.

- Green roofs may provide indirect ROI through stormwater compliance and roof membrane protection, but they require maintenance budgeting.

Maintenance and replacement cost implications

Maintenance and replacement are where many sustainability claims succeed or fail:

- Roofs with predictable inspection schedules and easy repairs often achieve their full design life.

- Systems that are difficult to service (poor access, complex penetrations, incompatible materials) tend to be replaced early, increasing waste and embodied emissions.

- Choosing a highly durable roof but neglecting flashings, drainage, and transitions is like buying a long-life engine and never changing the oil.

Climate-specific Roofing Selection Strategies

Climate-fit is one of the most reliable predictors of both sustainability and occupant comfort. The "best" eco-friendly roof is the one that minimizes energy use and replacement risk under local conditions.

Best roofing options for hot climates

In hot climates, prioritize strategies that reduce solar heat gain and protect materials from UV and thermal cycling:

- Cool roofs (high reflectance/emittance) for low-slope buildings with large roof areas.

- Reflective metal roofing with appropriate ventilation and insulation.

- Green roofs where water strategy and maintenance capacity exist; strong for urban heat and stormwater goals.

- Solar roofing often performs very well due to high solar resource—ensure roof orientation and shading are favorable.

Design notes: keep reflectivity durable (soiling matters), ensure continuous insulation, and detail ventilation paths correctly.

Cold-climate performance considerations

In cold climates, sustainability is driven by heat retention and moisture control:

- Prioritize airtightness, robust insulation continuity, and ice-dam-resistant detailing.

- Choose materials and assemblies proven under freeze-thaw cycling.

- Reflective surfaces may have smaller annual energy benefits, but durability and moisture management remain critical.

Solar can still be valuable in cold regions when winter sun access is good, but snow shedding, mounting details, and maintenance access should be planned.

Roofing solutions for mixed or extreme environments

Mixed climates and extreme environments demand balanced performance:

- Use assemblies that perform across seasons: insulation + airtightness + smart surface strategy (moderate reflectivity, durable materials).

- In extreme wind/hail regions, prioritize tested uplift and impact performance to avoid insurance-driven replacement cycles.

- Where wildfire risk is high, favor non-combustible roof assemblies and code-compliant details; the most sustainable roof is the one that survives.

Installation and Construction Considerations

Sustainable roofing performance is "made" as much on the jobsite as it is in the factory. Even a premium eco-friendly material can underperform if the roof assembly is poorly detailed, improperly ventilated, or incompatible with the building's moisture and insulation strategy. Professional installation is not just a quality preference—it is a sustainability requirement because it prevents early failure, avoids repeat construction, and preserves energy performance.

Importance of professional installation

Professional installers bring three sustainability-critical advantages:

- System-level detailing: Most roof failures happen at edges, penetrations, transitions, valleys, and flashings—not in the field of the roof. Experienced crews treat these details as primary performance zones.

- Moisture management discipline: Incorrect underlayment sequencing, unsealed fasteners, or missing drip edges can lead to trapped moisture, mold risk, and insulation degradation.

- Verified performance and warranties: Manufacturer warranties and code compliance often depend on approved installation methods, fastening patterns, and accessory components.

In practice, professional installation reduces the probability of leaks, wind uplift damage, and premature replacement—each of which carries a large embodied and financial cost.

Compatibility with insulation and ventilation systems

Eco-friendly roofing should be evaluated as an assembly: roof covering + waterproofing + air/vapor control + insulation + ventilation + drainage. Key compatibility considerations include:

- Insulation continuity: Gaps and thermal bridges can erase the expected energy benefits of "green" materials. Continuous insulation above the deck (where appropriate) often improves performance by reducing condensation risk and stabilizing temperatures.

- Ventilation strategy (for applicable roofs): Venting can reduce heat buildup and moisture accumulation, but it must be correctly sized and unobstructed. Poorly designed ventilation can be worse than none by pulling moist air into cold cavities.

- Air sealing: Airtightness often has a bigger effect on energy use than small differences between roofing materials. The roof-to-wall interface is a common weak point.

- Solar and roof system integration: PV systems require careful coordination of mounting hardware, flashing, and pathways to avoid creating long-term leak points.

A sustainable roof is one where thermal performance remains stable over time—meaning insulation stays dry and effective and ventilation (if used) keeps moisture from accumulating.

Common installation challenges and solutions

Several predictable challenges appear across sustainable roof types:

- Complex penetrations and rooftop equipment (commercial roofs):

- Challenge: multiple curb flashings and service traffic increase leak risk.

- Solution: designate walk pads, use robust flashing assemblies, and design maintenance access routes early.

- Heavy roofing systems (tile, slate, green roofs):

- Challenge: structural load and deflection issues can compromise performance and safety.

- Solution: confirm load capacity, include saturated weight for green roofs, and detail movement joints and fasteners correctly.

- Reflective/cool roof coatings:

- Challenge: adhesion failures due to improper substrate prep or moisture.

- Solution: rigorous cleaning, moisture testing, primer compatibility checks, and application within required temperature/humidity ranges.

- Metal roofing expansion/contraction:

- Challenge: oil canning, fastener fatigue, and noise if details ignore thermal movement.

- Solution: proper clip systems, expansion detailing, correct fastener selection, and compatible underlayments.

- Green roofs waterproofing and drainage:

- Challenge: root intrusion risk and blocked drains.

- Solution: root barriers, inspection chambers at drains, redundancy in waterproofing, and clear maintenance access.

Jobsite sustainability also includes waste management: accurate takeoffs, prefabrication where feasible, and sorting of scrap metals and packaging for recycling.

Maintenance, Repair, and Sustainability Over Time

A roof's sustainability profile is not fixed at installation—it evolves. Maintenance determines whether a roof achieves its expected service life, retains its energy performance, and avoids moisture-related damage that triggers early replacement and hidden carbon costs.

Routine maintenance requirements by material

Maintenance needs vary by system, but common patterns are:

- Recycled metal: periodic inspection of fasteners, sealants, and coatings; clearing debris from valleys and gutters; addressing scratches in protective finishes where corrosion could start.

- Cool roof membranes/coatings: inspections for punctures and seam integrity; cleaning to preserve reflectivity; re-coating on a planned cycle if required by the product.

- Clay/concrete tile and slate: checking for cracked or slipped units; maintaining flashings; ensuring underlayment integrity; careful foot traffic management to avoid breakage.

- Green roofs: vegetation health checks, irrigation (seasonal or establishment period), weed control, and frequent drain inspections to prevent ponding.

- Solar roofing: performance monitoring (to detect inverter issues or shading problems), occasional cleaning depending on local dust/pollen, and electrical safety checks.

- Wood shingles/shakes: moss/algae management, replacement of damaged pieces, ensuring adequate drying/ventilation, and compliance with any fire-resistance maintenance requirements.

- Synthetic recycled roofing: inspections of fasteners and sealants; checking for UV/weathering issues; verifying that accessories and flashings remain compatible over time.

The most sustainable roof is often the one with a realistic, budgeted maintenance plan—not the one with the most impressive brochure claims.

How proper care extends roof life

Small actions prevent big failures:

- clearing drains and gutters reduces water backup and edge damage,

- replacing a few cracked tiles prevents underlayment deterioration,

- resealing penetrations avoids moisture intrusion that can destroy insulation and decking,

- cleaning reflective surfaces helps preserve cooling energy savings.

Repairability is a sustainability asset. Roofs that can be repaired in localized areas—without full tear-off—typically produce less waste and retain more embodied value.

Impact of maintenance on environmental performance

Maintenance affects environmental performance through three mechanisms:

- Energy performance retention: wet or compressed insulation performs poorly; clogged ventilation reduces drying; dirty cool roofs lose reflectivity.

- Avoided premature replacement: extending service life reduces the embodied carbon and landfill waste of new materials.

- Reduced secondary damage: leaks often trigger replacement of interior finishes and mechanical components—impacts far larger than a simple patch.

Sustainability is not only about choosing a material with a good footprint; it is about keeping the roof working as designed.

Regulatory, Certification, and Compliance Considerations

Regulation increasingly shapes sustainable roofing choices. Codes define minimum safety and performance; green certifications provide structured pathways for documenting environmental benefits; and material transparency is becoming central to procurement decisions.

Green building certifications (LEED, BREEAM, etc.)

Green certifications typically reward roofing strategies that improve lifecycle outcomes, such as:

- energy performance improvements: cool roofs, high-performance insulation strategies, airtightness measures, and solar integration,

- stormwater management and heat island mitigation: green roofs and reflective surfaces,

- responsible materials: recycled content, verified sourcing, and products with environmental declarations,

- durability planning: designs that extend service life and reduce replacement frequency.

The certification system itself is less important than the discipline it encourages: set goals early, document product claims, and verify performance.

Local building codes and environmental regulations

Key code-driven roofing considerations often include:

- fire ratings and wildfire interface requirements: critical for wood roofing and for assemblies in high-risk zones,

- wind uplift and impact ratings: especially in hurricane and hail regions,

- cool roof requirements: some jurisdictions set minimum reflectance/emittance for certain building types or climate zones,

- stormwater rules: may incentivize or require onsite retention solutions where green roofs can contribute.

Compliance should be treated as a design input from day one, not a late-stage obstacle. Late changes often increase waste and cost.

Documentation and material transparency

Credible sustainability depends on evidence. Useful documentation may include:

- recycled content statements with clear definitions and chain-of-custody,

- Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) where available,

- Health and ingredient transparency disclosures (when relevant to project goals),

- warranty terms and tested performance data (wind uplift, fire rating, impact rating),

- end-of-life guidance (recycling streams, disassembly instructions).

Transparency reduces greenwashing risk and supports certification, permitting, and long-term asset reporting.

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Sustainable Roofing

Sustainable roofing is one of the rare building upgrades that can produce both environmental gains and financial value—when it's specified for climate fit and installed correctly.

Reduced energy consumption and emissions

Sustainable roofs reduce operational emissions by:

- lowering cooling loads through reflectivity and reduced heat absorption,

- supporting high-performance insulation and airtight assemblies,

- enabling on-site renewable generation with solar systems.

Because roofs have long service lives, even modest annual savings can compound into meaningful lifetime carbon reductions.

Improved indoor comfort and building performance

Comfort benefits show up as:

- more stable indoor temperatures and reduced overheating on top floors,

- lower radiant heat from hot roof surfaces in summer,

- fewer drafts and cold spots when the roof assembly is airtight and well insulated,

- improved resilience during heat waves and power disruptions (especially for buildings with passive cooling strategies or solar + storage).

A sustainable roof is often a quieter building, too—because better detailing reduces rattling, water ingress, and thermal stress movement.

Increased property value and market appeal

Market value can rise due to:

- lower operating costs and better energy ratings,

- reduced risk of major capital replacement (long-life roofs),

- improved insurability and resilience features in hazard-prone regions,

- alignment with corporate ESG goals and tenant expectations (commercial assets).

Sustainability is increasingly a "sellable" attribute, but the real driver is performance predictability.

Common Misconceptions About Eco-friendly Roofing

Misconceptions persist because roofing is often evaluated on upfront cost and appearance rather than lifecycle performance. Here are the most common myths—and what tends to be true in practice.

- Cost and affordability myths

- Myth: Eco-friendly roofing is always too expensive.

- Reality: Some sustainable options have higher upfront costs, but lifecycle cost can be lower due to energy savings, longer service life, and fewer repairs. In many hot climates, reflective roofing can deliver a relatively fast payback by reducing cooling demand.

- Durability and performance concerns

- Myth: "Green" materials don't last.

- Reality: Several eco-friendly options are chosen primarily for durability—metal, tile, and slate are longevity-driven solutions. Failure is more often tied to poor detailing, incompatible assemblies, or neglected maintenance than to the material category itself.

- Aesthetic limitations

- Myth: Sustainable roofs all look the same (usually bright white or ultra-modern).

- Reality: Sustainable choices span traditional and contemporary styles: slate and tile are classic; wood has a distinctive natural character where permitted; synthetics can mimic premium materials with less weight; solar can be integrated with a range of visual profiles; cool roof strategies increasingly offer color options while still targeting thermal performance.

How to Make the Final Roofing Decision

Choosing a sustainable roof is rarely about finding a single "best" material. It is a decision about system performance over time—how reliably the roof controls heat, manages water, resists local hazards, and avoids early replacement. The strongest outcomes come from treating the roof as a long-life building asset rather than a cosmetic surface.

Balancing sustainability, performance, and design

A practical way to balance priorities is to score options across three dimensions:

- Sustainability (lifecycle impact): embodied emissions, recycled/renewable content, service life, end-of-life recovery, and operational energy effects.

- Performance (risk and resilience): leak resistance, wind uplift, fire/impact performance, corrosion resistance, and compatibility with the building's moisture strategy.

- Design (fit and acceptance): architectural intent, neighborhood or historical constraints, visibility of solar, and how details (ridges, edges, penetrations) will look when built.

In real projects, trade-offs are normal. For example, a roof with high recycled content is not sustainable if it is poorly suited to local wind loads and fails early. Likewise, a long-life material can lose much of its advantage if the assembly traps moisture and destroys insulation performance.

A helpful rule: prioritize the failure modes that cause premature replacement in your location (wind, hail, fire, ponding water, freeze-thaw, corrosion), then optimize environmental impact within the set of solutions that can reliably survive those stressors.

Prioritizing goals based on project type

Different projects should weight goals differently because risk tolerance, ownership horizon, and operational priorities vary.

- Owner-occupied residential (long-term):

- Emphasize longevity, low maintenance, indoor comfort, and future flexibility (solar readiness, easy repair).

- A slightly higher upfront cost can be rational if it meaningfully reduces replacement likelihood.

- Residential development (shorter hold):

- Emphasize code compliance, predictable installation quality, broad buyer appeal, and clear warranties.

- Select systems that minimize callbacks (leaks at penetrations, poor attic ventilation, flashing failures).

- Commercial owner-operator:

- Emphasize operational energy savings, roof access/serviceability, warranty robustness, and risk reduction.

- Cool roofs, high-performance insulation assemblies, and solar can create strong business cases when aligned with maintenance capacity.

- Commercial investor/portfolio:

- Emphasize standardized systems, documented performance, and lifecycle planning that supports predictable capital forecasting.

- Favor solutions with consistent contractor availability and clear end-of-life handling.

- Public or institutional buildings:

- Emphasize resilience, public value (stormwater control, heat island reduction), and documentation for sustainability reporting.

- Green roofs and solar often align well when maintenance and access are planned from the start.

Creating a decision checklist for buyers and builders

Below is a concise checklist that works for both buyers and builders. It is designed to prevent the common “good material, bad system” outcome.

- Project context

- Define the ownership horizon (5, 15, 30+ years) and risk tolerance.

- Confirm roof slope, drainage approach, and access needs (maintenance traffic, rooftop equipment).

- Identify local hazards: wind, hail, wildfire, heavy snow/ice, salt air, extreme heat.

- Performance requirements

- Confirm required fire rating, wind uplift rating, and impact performance where relevant.

- Specify a complete water management plan: underlayment/membrane, flashing strategy, drainage paths, overflow provisions.

- Ensure compatibility with insulation and air/vapor control strategy (avoid condensation traps).

- Sustainability and documentation

- Require recycled content and sourcing claims to be documented (not marketing language).

- Prefer materials with realistic end-of-life recovery pathways in your region.

- Consider whether the roof supports energy goals (cool roof properties, solar readiness, thermal stability).

- Cost and value

- Compare options using cost per year of service, not only installed price.

- Budget for maintenance: inspections, coatings, vegetation care (if green roof), solar monitoring.

- Align roof life with major add-ons (solar, skylights, mechanical upgrades) to avoid early tear-off.

- Execution quality

- Select installers with verified experience in the chosen system.

- Require pre-installation coordination for penetrations, curbs, and attachment points.

- Plan commissioning/close-out: photos of critical details, as-built drawings, maintenance schedule.

Future Trends in Eco-friendly Roofing Materials

Eco-friendly roofing is shifting from "alternative materials" to high-performance roof systems that combine durability, energy control, and data-driven maintenance. The future is less about one breakthrough product and more about integrated solutions that reduce risk and emissions simultaneously.

Innovations in materials and coatings

Several innovation directions are accelerating:

- Longer-lasting reflective coatings: improved resistance to soiling and weathering helps maintain reflectivity, preserving cooling savings without frequent recoating.

- Lower-carbon binders and formulations: manufacturers are working to reduce embodied emissions in cementitious and polymer-based products through material substitution and process improvements.

- Improved impact and weather resistance: especially relevant in hail-prone regions, where better impact performance can reduce replacement cycles and insurance-driven waste.

- Design-for-repair and modularity: systems that allow targeted repairs—rather than full replacement—will increasingly be viewed as "sustainable by design."

The overarching theme is durability with performance retention: roofs that stay efficient as they age, rather than starting strong and degrading quickly.

Smart roofing and energy-integrated systems

"Smart roofing" is emerging as a practical tool for extending service life and preventing hidden damage:

- Leak detection and moisture monitoring: sensors can identify problems early, reducing the scope of repairs and preventing insulation failure.

- Predictive maintenance for large portfolios: data from inspections, sensors, and weather events can guide targeted interventions rather than reactive replacements.

- Energy-integrated roofs: solar is becoming more standardized, and the next step is tighter integration with roof design—attachment methods, wiring pathways, and service access that reduce leak risk and simplify maintenance.

- Hybrid approaches: combinations such as cool roof membranes optimized for PV performance, or carefully designed green roof + PV arrangements where structure and maintenance planning support it.

- The sustainability payoff is twofold: lower operational emissions and fewer premature replacements due to unmanaged small failures.

Growing demand for sustainable construction solutions

Demand is rising due to converging forces:

- Regulatory pressure: building performance standards, heat mitigation rules, and stormwater requirements are pushing roof choices toward higher-performing systems.

- Financial signals: energy cost volatility, insurance pressures in hazard zones, and ESG reporting expectations increasingly reward resilient, documented roof solutions.

- User expectations: comfort during heat waves, indoor air quality, and visible sustainability features (like solar) are influencing both residential buying behavior and commercial leasing.

As these pressures intensify, "eco-friendly" will increasingly mean measurable performance—not just material claims.

A sustainable roof demands smart, integrated choices: the right material for your climate and structure, plus excellent installation, detailing, and maintenance planning to deliver reliable performance for decades.

- Core Decision Criteria

- Climate & hazard resistance (wind, hail, fire, snow, corrosion)

- System-level thermal performance (reflectivity, insulation, moisture control)

- Long service life with easy repairability and low waste

- Proven sustainability credentials (sourcing, recycled content, end-of-life recyclability)

- Strong lifecycle value (energy savings, low maintenance, delayed replacement, resilience)

- Key Long-Term Benefits

- Reduced energy use and emissions year after year

- Better comfort and lower overheating risk

- Fewer repairs and replacements

- Greater building protection and asset value

- Alignment with green standards and market expectations

Sustainable roofing is a strategic investment: it protects the entire building envelope, preserves insulation effectiveness, and avoids early capital costs—all while combining function, aesthetics, and genuine environmental impact.

At Hangzhou Chuanya Building Materials Co., Ltd., we manufacture durable, energy-efficient roofing solutions engineered for exactly these priorities. Contact us to select a high-performance, eco-friendly roofing system built to last.

English

English Español

Español عربى

عربى

Email:

Email: Phone:

Phone: Adress:

Adress: